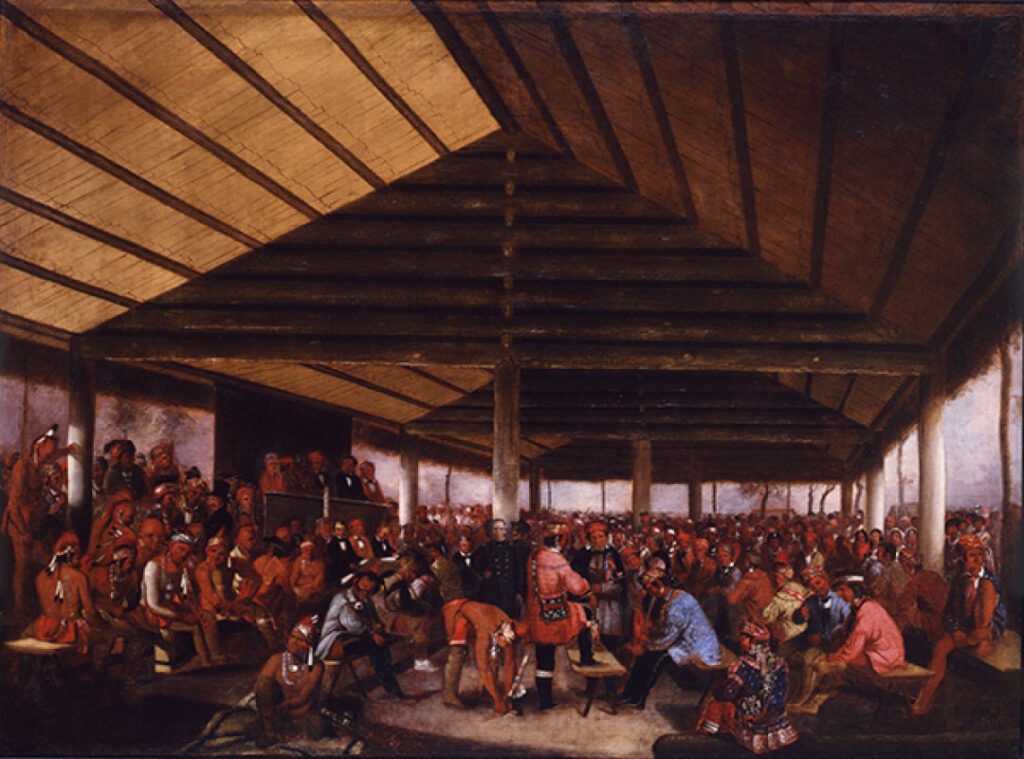

Artwork: Indian Council of 1843 at Tallequah by John Mix Stanley. Source: Smithsonian Museum of American Art

Once the final detachments of Cherokee reached their new home in Indian Territory in 1839, they faced the challenge of rebuilding and reunifying their government, communities, and families, having lost a quarter of their population along the journey. The eastern Cherokee joined together with the western, or Old Settler, Cherokee and the Treaty Party Cherokee who had relocated to Indian Territory in 1835. Together they passed an Act of Union in 1839. Then they ratified a constitution, which re-created the three branches of government: executive, legislative, and judicial.

Once the government had been reestablished, the Cherokee National Council turned its attention to national programs. In 1841, it passed the Public School Act, which established a universal public education program. The council also opened male and female seminaries, institutions of higher learning that offered free education to Cherokee students. The new Cherokee tribal lands were held communally and governed by the Cherokee Nation government.

Cherokee commerce began to flourish, with mercantile businesses, mills, and successful farms appearing throughout the Nation. Cherokee people thrived as they became acclimated to their new homeland. This renewed golden age of Cherokee Nation would, however, be short-lived.