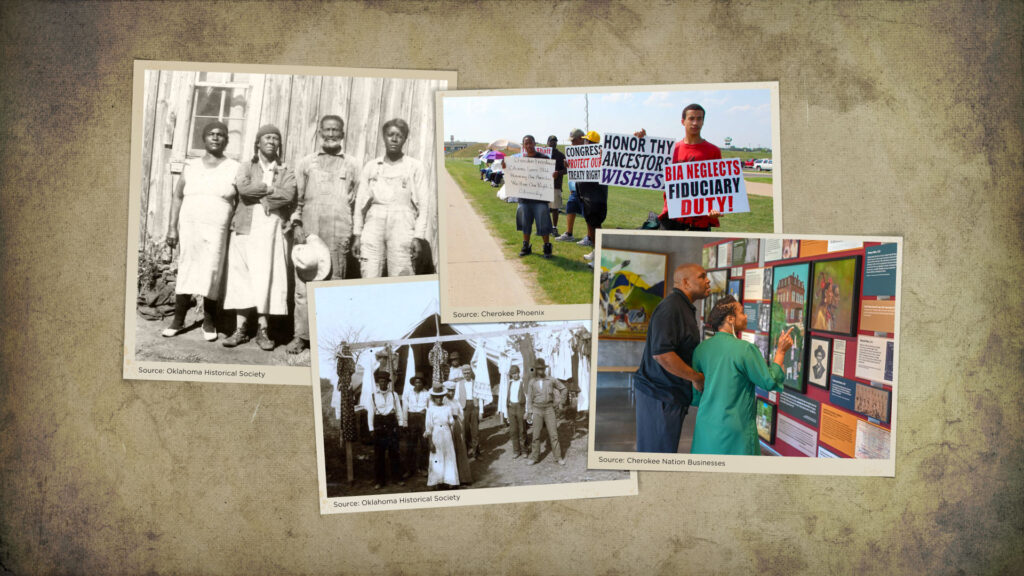

Source: Oklahoma Historical Society

Home / Culture & History / Cherokee Freedmen

The history of Cherokee Freedmen began long before the Treaty of 1866. Since the Cherokee people’s earliest involvement in slavery more than two centuries ago, people enslaved by Cherokees faced the same tragedies as the tribe – including Cherokee Removal – but had no rights. Emancipation in 1866, however, did not end the struggle of Cherokee Nation’s freed slaves. Instead, it would take many generations for these Cherokee Freedmen and their descendants to restore their treaty-protected rights as Cherokee Nation citizens.

Slavery in Cherokee Nation

Artwork: Two children near cotton, photographer unknown. Source: Oklahoma Historical Society.

The enslavement of Black people among Cherokees began after it was introduced by Europeans in the 17th century. Forms of captivity already existed among the tribe, but the slavery of African-descended people was especially exploitive and dehumanizing. By the early 1800s, elite, mostly bicultural Cherokees had begun to adopt the ideas and lifestyle of American plantation owners, including the use of Black slaves in agriculture.

Artwork: Two children near cotton, photographer unknown. Source: Oklahoma Historical Society.

Some Cherokees, such as Joseph Vann at his Diamond Hill plantation in present-day Georgia, soon began to grow individual wealth from the enslavement of Black people. Vann was not alone. By 1835, slaveholders such as John Ross, Lewis Ross, David Vann, and John Ridge — Cherokee leaders, all — comprised a distinct economic upper class within Cherokee Nation. This shift away from traditional Cherokee culture was agreeable to the U.S. government, but it did not stop Cherokee Removal.

Enslaved people joined their Cherokee owners on the Trail of Tears in 1838 – 39. They likely translated for their owners and performed physical labor in addition to facing hardship and illness. Arriving in Indian Territory, they helped Cherokees rebuild their lives, homes, and farms. This likely widened the class divide, as elite Cherokees with enslaved labor more quickly financially recovered and rebuilt. The post-Removal years were marred by violence between Cherokees who supported signers of the Treaty of New Echota (1835) and those vehemently opposed to Removal. During this time, Cherokee Nation began to outlaw many of the small freedoms previously possible for enslaved people.

War & Emancipation

Artwork: A plank residence in the Arkansas River Bottom, photographed by Allison Aylesworth. Source: Oklahoma Historical Society.

The Civil War came to Cherokee Nation in 1861. The divide between the affluent, bicultural families and more conservative or traditional Cherokees widened over chattel slavery. Though the lines were not always clear-cut, wealthier slaveholding Cherokees tended to support the Confederacy. Others sided with the Union because they opposed the wealthier Cherokees, disagreed with slavery in Cherokee Nation or had other reasons.

Many enslaved people found themselves on the move again, with owners retreating from Cherokee Nation to Confederate-supporting Texas and Arkansas. Those who stayed in Indian Territory were at the mercy of fighting between Northern and Southern sympathizers. Other slaves escaped to Kansas. There, some men volunteered for the Union, including in the 1st Kansas Colored Infantry – the first Black regiment to see combat in war. Though the Cherokee National Council voted in February 1863 to free all slaves within Cherokee Nation, the rights of emancipation would not be enforced until the Cherokee Treaty of 1866. This document identifies Cherokee Freedmen as Cherokee Nation citizens afforded all the same rights as Native Cherokees.

However, Freedmen faced barriers to citizenship, including a deadline to return to the Nation. In 1875, the Cherokee people elected Freedman Joseph Brown of Tahlequah District to the Cherokee National Council. He is believed to be the first of at least seven Freedmen elected to the council between 1875 and 1906. Inequality, however, remained in many facets of life.

Cherokee Freedmen who served on the Cherokee National Council:

Joseph Brown, Tahlequah District, 1875–1877

Rev. Jack Brown, Illinois District, 1885–1887

Frank Vann, Illinois District, 1887–1889

Jerry Alberty, Cooweescoowee District, 1889–1891

Joseph “Stick” Ross, Tahlequah District, 1893–1895

Ned Irons, Tahlequah District, 1895–1897

Samuel Stidham, Illinois District, 1895–1897

Demanding Recognition

Artwork: Cherokee Nation citizen Marilyn Vann remains an advocate for the rights of Cherokee Freedmen descendants. She was appointed to the Cherokee Nation Environmental Protection Commission in 2021. Source: Marilyn Vann.

Freedmen continued to face indignities in the years before Oklahoma statehood. In 1883, the Cherokee National Council passed a law restricting per capita payments from the sale of tribal lands to citizens who possessed Cherokee blood. Though vetoed by Cherokee Nation Principal Chief Dennis Bushyhead, the National Council overturned it. During the Dawes enrollment, Freedmen were placed on a separate list from other Cherokee Nation citizens.

With the passage of the Curtis Act of 1898, Cherokee Nation’s government and institutions were largely dissolved by the end of 1906. Political winds, however, shifted in favor of tribal self-determination in the late 1930s. In 1971, Cherokee Nation citizens, including Freedmen descendants, received citizenship cards and cast their votes for Cherokee Nation Principal Chief. This advancement was short-lived. The tribe canceled Freedmen’s citizenship in 1983, and disenfranchised Freedmen descendants took their suits to federal and tribal courts. In 2007, Cherokee voters — excepting Freedmen descendants — voted to amend the constitution limiting citizenship to by-blood Cherokees.

In August 2017, U.S. District Judge Thomas Hogan made his landmark ruling that “Cherokee Freedmen have a present right to citizenship in the Cherokee Nation that is coextensive with the rights of Native Cherokees” under the Treaty of 1866. Cherokee Nation did not appeal the decision and began processing Freedmen descendants’ citizen applications. Marilyn Vann, a leader in the Freedmen community, filed to run for an at-large seat on the Tribal Council of the Cherokee Nation in February 2021. That same month, the Cherokee Nation Supreme Court ruled the words “by blood” be stricken from the Cherokee Nation Constitution and its laws. Today, more than 15,000 descendants of Cherokee Freedmen are registered Cherokee Nation citizens.

A Timeline of Cherokee Freedmen History

Many events which shaped the history of the Cherokee Nation, including Cherokee Removal and the Civil War, are the lived experiences of Cherokee Freedmen and their descendants. In fact, the Cherokee Story would be diminished without Cherokee Freedmen, who fought for decades, in courtrooms and courts of public opinion, to restore their right to full citizenship.

Click or tap any date to read about treaties, laws and major events that shaped the destiny of Cherokee Freedmen.

In the 1730s, a Cherokee delegation enters into an agreement with British officials to return captured runaway Black slaves to their British owners.

The 1827 Constitution of the Cherokee Nation is passed, declaring “no person who is of negro or mulatto parentage, either by the father or mother side, shall be eligible to hold any office of profit, honor or trust, under this Government.” It also states only free male citizens “except negroes, and descendants of white and Indian men by negro women” are entitled to vote in elections.

Congress passes the Indian Removal Act.

The Treaty of New Echota is signed by unauthorized Cherokees, forcing the removal of all Cherokees to lands west of the Mississippi River.

Black people enslaved by Cherokees join them in the Cherokee Removal to Indian Territory.

Cherokee Nation’s 1839 Constitution is ratified, reaffirming the inferior status of residents of African heritage. This was soon followed by “An Act to Prevent Amalgamation with Colored Persons,” making intermarriage between Whites or Indians with a person of color illegal and punishable.

The American Civil War begins with the Battle of Fort Sumter near Charleston, South Carolina.

Though previously declared neutral, the Cherokee Nation makes a treaty with the Confederacy.

US President Abraham Lincoln issues the Emancipation Proclamation freeing Black slaves in Confederate states. It does not apply to sovereign nations, including Cherokee Nation.

The Cherokee National Council revokes its treaty with the Confederacy and passes an act to free slaves held by its citizens. Fines are set against owners holding slaves after June 25, 1863.

Confederate General Robert E. Lee surrenders to the Union at Appomattox, Virginia, signaling the conclusion of the Civil War. Cherokee leader Stand Watie becomes the last Confederate general to surrender on June 23, 1865.

Cherokee Nation and the US government sign the Treaty of 1866, abolishing slavery in the Cherokee Nation and guaranteeing Freedmen and their descendants “the rights of native Cherokees.”

Joseph Brown is elected to the Cherokee National Council representing Tahlequah District. He is the first known Cherokee Freedmen to be elected to a Cherokee Nation office and serves from 1875-1877.

Congress passes the Dawes General Allotment Act, authorizing the US to break up treaty-guaranteed tribal lands held in common and parcel them into allotments to give to the tribes’ citizens. Citizens must enroll with the Office of Indian Affairs to receive an allotment.

Cherokee Nation Colored High School opens at Double Springs, northwest of Tahlequah, in Cherokee Nation. Approximately 25 students were enrolled.

US President William McKinley signs the Curtis Act of 1898 into law seeking to dismantle the tribal governments by March 1906.

Oklahoma is admitted as the 46th state in the Union.

Cherokee Nation citizenship cards are issued to descendants of Cherokees listed on the Dawes Roll. Cherokee Freedmen participate in the 1971, 1975 and 1979 tribal elections.

Cherokee Nation citizens vote to approve a new constitution stating that all Cherokees listed on the Dawes Roll and their descendants are Cherokee Nation citizens.

Freedmen descendants are informed their Cherokee Nation citizenship is revoked after the tribe revises citizenship requirements to include a Certificate Degree of Indian Blood card. The Dawes Roll did not include blood degrees for Freedmen, whose descendants are turned away from the polls during the June 18, 1983, tribal election.

Rev. Roger H. Nero, who was 2 years old when he was listed as a Cherokee Freedmen on the Dawes Roll, files a federal suit with 16 other Freedmen plaintiffs against Cherokee Nation for denying both his right to vote in the 1983 tribal election and his access to tribal benefits. The case was dismissed.

The Tenth Circuit Court of Appeals affirms the dismissal of the Nero suit on grounds that the dispute was a tribal affair outside of the court’s jurisdiction.

Bernice Roger Riggs loses her suit filed in 1997 against Cherokee Nation registrar Lela Ummerteskee after she is denied Cherokee Nation citizenship based on the law limiting tribal citizenship to by-blood Cherokees.

Cherokee Nation citizens vote to remove the requirement of federal approval on future amendments to the tribe’s constitution or on a new constitution. Freedmen descendants are denied participation in the vote.

A group of Cherokee Freedmen contacts the Bureau of Indian Affairs (BIA) to protest the tribe’s May 24 general election.

Cherokee voters approve a new constitution replacing the 1975 Constitution. The BIA does not approve, but later decides not to challenge the results of the May 2003 election.

Marilyn Vann sues the US Department of Interior, Cherokee Nation and officials for both in federal court contending that the May 2003 general election was invalid because Freedmen were not allowed to vote.

Lucy Allen sues the Cherokee Nation Tribal Council, tribal registrar, and registration committee in Cherokee Nation court challenging the tribe’s authority to strip the citizenship of Dawes enrollees’ descendants, who are defined as citizens based on the 1975 Constitution.

The Cherokee Nation Judicial Appeals Tribunal rules in Allen’s favor and reverses the 2001 decision on Riggs v. Ummerteskee.

The Cherokee Nation Tribal Council votes 13-2 to allow Cherokee Nation citizens to vote on an amendment to the Constitution requiring Indian blood for Cherokee Nation citizenship.

Cherokees vote in a special election to amend the Constitution to limit citizenship to those with Indian blood.

Cherokee Nation District Judge John T. Cripps approves an application for a temporary injunction against the March 3 constitutional amendment and reinstates Freedmen as citizens.

US Rep. Diane Watson of California introduces US House Resolution 2824, which proposes to sever US relations with Cherokee Nation, including federal funding, until the tribe restores the rights of Cherokee Freedmen. The bill doesn’t pass.

Members of the Congressional Black Caucus oppose a Native American housing assistance bill unless it includes provisions preventing Cherokee Nation from receiving any funding from the bill until the tribe recognizes Freedmen as citizens.

Cherokee Nation files a lawsuit asking the US District Court for the Northern District of Oklahoma to resolve the dispute with Freedmen descendants by confirming that in 1896, Congress “unilaterally modified the Treaty of 1866 and nullified Freedmen and their descendants’ tribal citizenship.”

Cherokee Nation District Judge John T. Cripps rules in Nash v. Cherokee Nation Registrar that the descendants of Cherokee Freedmen enrolled by the Dawes Commission are entitled to tribal citizenship and the equal rights in place before the 2007 constitutional amendment.

The Cherokee Nation Supreme Court reverses and vacate Cripps’ January ruling, stating that Cherokees have the right to amend their Constitution and set citizenship requirements.

The US Department of Interior files a counterclaim against Cherokee Nation for a judgment declaring the Treaty of 1866 “provided and continues to provide” Freedmen descendants the rights and privileges of tribal citizenship. In May, the US District Court for the Northern District of Oklahoma grants the tribe’s motion to amend its complaint filed in 2009.

Oral arguments are held in the now combined Vann and Nash cases to determine whether or not the Treaty of 1866 grants citizenship rights to the Cherokees’ former slaves and their descendants.

US District Judge Thomas Hogan rules that “Cherokee Freedmen have a present right to citizenship in the Cherokee Nation that is coextensive with the rights of Native Cherokees.” Further, “the Freedmen’s right to citizenship does not exist solely under the Cherokee Nation Constitution and, therefore, cannot be extinguished solely by amending the Constitution.”

Cherokee Nation Supreme Court Chief Justice John Garrett order the tribal registrar and government to begin processing citizenship applications of eligible Freedmen. The order further states Freedmen citizens can run for tribal office.

Rodslen Brown, a Cherokee Nation citizen of Freedmen descent, is appointed as Cherokee Nation community liaison to the Cherokee Freedmen community.

Eight Cherokee Nation citizens ask the tribe’s Supreme Court to withdraw Garrett’s order and direct Hembree to appeal Hogan’s ruling.

The Cherokee Nation Supreme Court denies the motion to compel Hembree to appeal Hogan’s ruling.

Cherokee Freedmen descendant Marilyn Vann files to run for an at-large seat on the Tribal Council of the Cherokee Nation. Despite the provision in the Cherokee Nation Constitution stating candidates for public office must be a by-blood citizen to be eligible to run for office, Vann is allowed to run and appears on the general election ballot.

The Cherokee Nation Supreme Court, in the final court order in the Freedmen legal battle, orders the phrase “by blood” removed from the Cherokee Nation Constitution and other laws, rules, regulations and policies of the Nation.

US Secretary of the Interior Deb Haaland approves a new Cherokee Nation Constitution that ensures the protection of Freedmen citizenship and rights.

Appointed by Cherokee Nation Principal Chief Chuck Hoskin Jr. to Cherokee Nation’s Environmental Protection Commission, Marilyn Vann becomes the first Cherokee Nation citizen of Freedmen descent to hold a tribal governmental office.

Melissa Payne, daughter of the late Rodslen Brown and an advocate of Cherokee Freedmen recognition, fills the advisory seat of Cherokee Nation community liaison to the Cherokee Freedmen community, previously held by Brown.

Media Contact

Whitney Dittman

whitney.dittman@cn-bus.com

918.384.6714

Sign up and get our monthly events newsletter delivered to your inbox along with updates on the latest news, upcoming special events and information about authentic Cherokee experiences.