Author: Karen Shade

Photographer Jennie Fields Ross Cobb occupies a special place in Cherokee Nation’s history.

Between about 1896 to 1906, she took her small box camera and photographed the people and places she knew. The result is a small collection of images offering a glimpse of life in Indian Territory before Oklahoma statehood in 1907. Refreshingly candid, Jennie’s surviving work along with her efforts to preserve a piece of Cherokee history have secured Jennie’s identity as the first-known Native American female photographer in Indian Territory.

A rare portrait of Jennie Ross Cobb, circa 1945, the first acting curator of Hunter’s Home historical site. Image courtesy of the Hunter’s Home Archives.

Born into the renowned Ross family at Park Hill, Indian Territory, on Dec. 26, 1881, Jennie was the great-granddaughter of John Ross, the Cherokee Nation principal chief who fought to keep his tribe in their ancestral lands and united after the Removal. He died in 1866, but his descendants carried on his legacy of service. Robert Bruce Ross Sr., Jennie’s father, served the Cherokee Nation and community in several roles, including Cherokee Nation treasurer and chairman of the Cherokee Commission to the Dawes Commission. He and his wife, Frances Thornton Ross, brought their youngest children to live at the historic Hunter’s Home when they became caretakers of the property. Jennie entered the Cherokee National Female Seminary in nearby Tahlequah around the same time.

Jennie Ross Cobb used this camera and negative frames to produce a collection of photos capturing her life in Cherokee Nation in the last decade of Indian Territory. Image courtesy of the Oklahoma Historical Society.

Photography was the province of professionals for decades until manufactures started making units that put the evolving artform into amateur hands. It was particularly marketed as an exciting new hobby for young women. When Jennie received her first camera, she captured her fellow seminarians strolling to town and enjoying each other’s company. Jennie also photographed Hunter’s Home. Sometimes, her family were within frame, but she also focused on the rooms and the house.

After her graduation in 1900, she became a teacher in Cherokee Nation’s public schools in several Cherokee communities, including Paw Paw and Christie. By this time, however, she had largely set photography aside. She married a land surveyor named Jesse Clifford Cobb in 1905, and they later moved to Arlington, Texas, to raise their daughter. Jennie owned and operated a floral shop there for many years.

In 1948, the state of Oklahoma purchased Hunter’s Home to preserve the 1845 plantation site. Jennie and her siblings had advocated many years to save the place, and she campaigned to become its first “hostess.” When she earned the post, Jennie set to work locating the home’s original furnishings. Her memories living in the home helped, but so did her old photos.

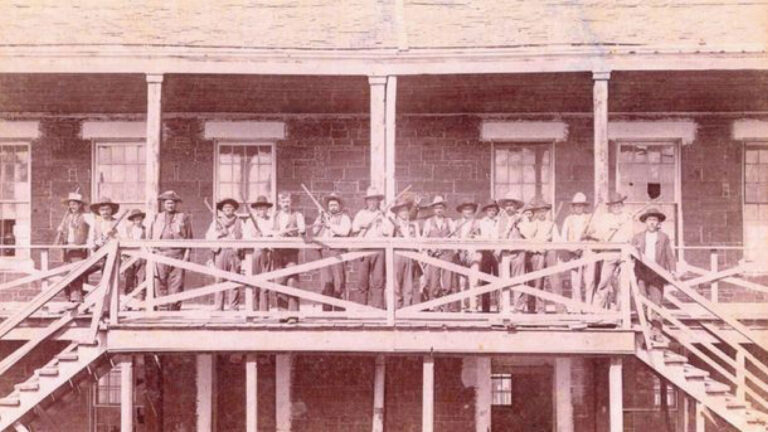

Friends of Jennie Ross Cobb enjoy watermelon on a summer afternoon near Park Hill, circa 1896-1906. Image courtesy of the Oklahoma Historical Society.

Jennie found in the attic one of her old cameras and some of the glass plate negatives she processed in a downstairs bedroom closet so many years before. She was the site’s curator until her death in 1959, but her commitment to preservation can still be seen in the objects she found and restored to the site. Informal, casual and unguarded, Jennie’s images also resonate with viewers today. They tell the story of her unique experience as a young woman from a highly influential and progressive Cherokee family in those golden days before statehood swept over Indian Territory.

“Through the Lens: The Photographic Legacy of Jennie Ross Cobb” can be seen at the Cherokee National History Museum through March 2021.