Author: Karen Shade-Lanier

Sequoyah was about 80 years old when he left his family and home in Cherokee Nation, Indian Territory, in 1842. Whether or not he knew it would be for the last time is next to impossible for us to know. The inventor of the written form of the Cherokee language left nothing in his own hand explaining why he would travel to Mexico during a turbulent revolutionary period. What we do have is an article printed in the Cherokee Advocate on June 26, 1845. In his account, a Cherokee guide named Oo-chee-ah tells how Sequoyah came to him in the spring of 1842 and asked for his help. A short time later, Oo-chee-ah, Sequoyah, and seven other men (among them Sequoyah’s son, Teesee Guess) left Tahlequah on horseback in search of Cherokees in Mexico.

Sequoyah’s cabin near Sallisaw, Oklahoma, ca. 1912 (Muriel Wright Collection). Courtesy of the Oklahoma Historical Society

The first half of the nineteenth century brought catastrophic change that scattered the Cherokee people. Prior to removal, Cherokee Nation covered an area of present-day southeastern U.S., including parts of Alabama, Georgia, Tennessee, and North Carolina. Faced with ever increasing pressure to quit their ancestral lands, some Cherokees hoped to escape white encroachment by going West in the decades before forced removal in 1838-39.

In 1819, a number of Cherokee families split from a group living in Arkansas Territory. They settled in East Texas, then under Spanish rule. Following Mexican independence in 1821, these Cherokees sought land grants from the Mexican government. Then came the Texas Revolution, and the Cherokees were driven out. Some were believed to have fled to Mexico. It was these Cherokees, many historians believe, who Sequoyah sought.

In the 1845 Cherokee Advocate article, Oo-chee-ah recalls that after crossing the Red River, the journey became arduous because of tensions between the Texans and Mexican government. Travel was also complicated by Sequoyah’s failing health. The story continues that an ailing Sequoyah was brought to a Cherokee village about ten miles near the Mexican village of San Cranto. Sequoyah sent Oo-chee-ah to a town they passed months before and where their horses were stolen. En route, Oo-chee-ah learned that Sequoyah died. In May 1845, Pierce M. Butler, the Indian Agent at Fort Gibson, forwarded letters from a Cherokee messenger, Oo-no-leh, to Commissioner of Indian Affairs Thomas Hartley Crawford. “He is dead without doubt,” Oo-no-leh wrote of Sequoyah’s fate.

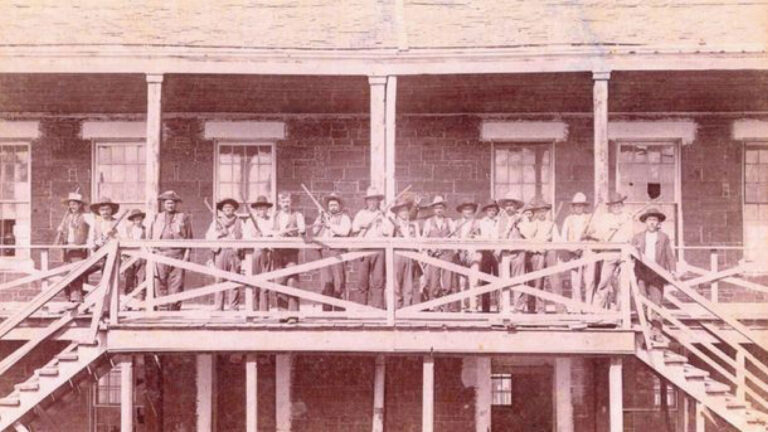

The search for Sequoyah, however, didn’t end there. In 1938, Cherokee Nation Principal Chief J.B. Milam funded an expedition to Coahuila, Mexico, to find the grave in 1938. The mission was unsuccessful. In 1952, the Tahlequah Star-Citizen printed an article alleging that Tahlequah natives Omer and Mary Morgan found his grave near the “Old Cherokee Ranch,” also in Coahuila. With the help of Cherokee Nation Principal Chief W.W. Keeler, the Morgans received a permit to excavate the graves and returned in 1953, but neither of the graves were proven to be Sequoyah’s.

Omer and Mary Morgan, of Tahlequah, Oklahoma, believed they found Sequoyah’s grave in the 1950s when they came upon this boulder near Coahuila, Mexico, etched with marks resembling Cherokee syllabary characters. Photo courtesy of the Cherokee National Archives, Park Hill, Oklahoma.

Citizen historian Gertrude Ruskin took up the search in Mexico in the 1960s. She conceded defeat, but wrote about her findings in her book Sequoyah, Cherokee Indian Cadmus (1970). In 2001, it was widely reported that a Texas doctor claimed to have found Sequoyah’s grave in a three-chambered cave near Zaragoza, Coahuila, Mexico, but this claim, too, was never proven. Like his life, Sequoyah’s death is an enduring mystery which may never be solved.

In honor of the Cherokee Syllabary Bicentennial, the “Sequoyah’s Last Journey” exhibit can be seen at Sequoyah’s Cabin Museum in Sallisaw, Oklahoma, through December 31, 2021.